"Come Get Me, Coward": When Presidents Start Daring Superpowers, the Script's Already Burnt.

Or: How to document the exact moment international law became a suggestion, three countries at a time.

The Setup.

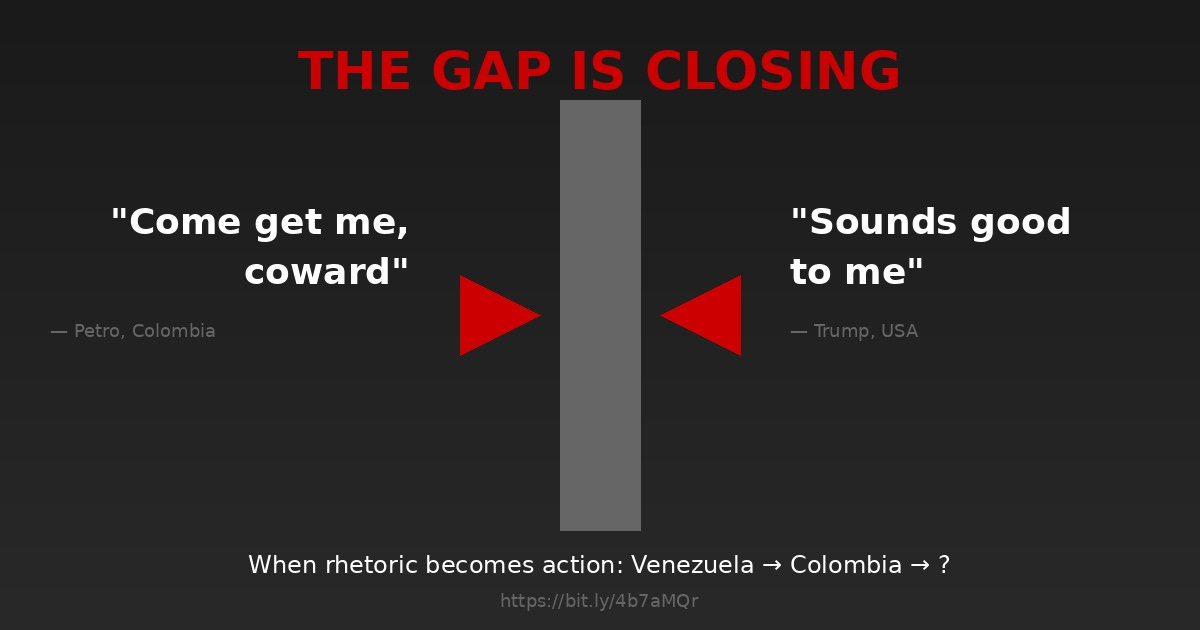

Colombian President Gustavo Petro watched Trump’s forces grab Maduro from Venezuela over the weekend, went live, and said: “Come get me, coward. I’m waiting for you here.”

Not through diplomatic channels. Not in a carefully worded statement. A public dare to the world’s biggest military: Try it. I’m right here.

Now here’s the bit that should terrify you: Trump already told us he would.

When asked about a US operation in Colombia, Trump said: “Sounds good to me.”

We’re not talking about threats anymore. We’re watching the gap between “I might” and “I did” disappear in real-time. And nobody’s acting surprised because somehow, in the last twelve months, this became normal.

Let me show you the mathematics.

Three Countries, One Pattern.

Venezuela: US Delta Force captured sitting President Nicolás Maduro and flew him to America. A head of state, removed by foreign military action. Not regime change through sanctions or coups—just straight-up abduction.

Greenland: Trump floated annexing it. Repeatedly. Taking sovereign territory from Denmark, a NATO ally, became dinner-table conversation.

Colombia: Trump said Petro “better wise up, or he’ll be next. He’ll be next. I hope he’s listening.”

The exact same language he used about Maduro before the raids started.

Notice what’s happening? Each action expands what’s possible tomorrow. Greenland made Panama Canal takeover discussions normal. Venezuela made Colombia plausible. Whatever’s next will make something currently unthinkable seem reasonable by Thursday.

This is how boundaries dissolve. Not with announcements—with precedent.

And here’s where the pattern gets interesting: it’s not about choosing targets at random. A small number of actors are driving the overwhelming majority of regional outcomes. Left-wing governments targeted systematically. Right-wing allies protected and pardoned. That’s not coincidence—that’s method.

The Excuse Menu.

Venezuela? Drugs and dictatorship.

Greenland? Strategic minerals.

Colombia? Trump says it’s “run by a sick man who likes making cocaine and selling it to the United States.”

The justification changes. The mechanism stays identical.

You could spin a globe blindfolded, point anywhere, and construct a plausible intervention using Trump’s established framework. The Maldives? Chinese influence. Madagascar? Rare earths. Iceland? “Protecting NATO interests” (whilst simultaneously threatening Greenland, another NATO territory, but don’t think about that bit too hard).

The pretext is decorative. It’s the wrapping paper on the same box every time.

Here’s 2026’s contribution to political language: “Anti-drug operations” instead of “we’re abducting heads of state now.”

The International Response (Brace Yourself).

After Venezuela, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Uruguay and Spain released a joint statement calling it “an extremely dangerous precedent for peace and regional security” that “contravenes fundamental principles of international law.”

Strong words. Principled stance. Profound concern expressed.

Then? Absolutely fuck all.

No sanctions. No coordinated response. No consequences. Just six countries confirming that international law is now the geopolitical equivalent of asking someone nicely to stop.

Which means the next operation faces even less resistance. You’ve just watched the boundary shift in real-time.

Now, when examining patterns like this, you’ve got to ask: is this coordinated malice or systematic incompetence? Are we watching deliberate imperial strategy, or are we watching people stumble into consequences they never modelled? The answer probably matters less than the outcome—but it’s worth considering whether Trump’s actually planned this sequence or whether he’s just following the path of least resistance, doing what works until something stops him.

Petro’s Gambit.

Here’s what makes Petro’s response strategically fascinating: he’s not playing defence. He’s forcing the question into daylight before the bombs drop.

“Come get me. I’m waiting for you here. Don’t threaten me, I’ll wait for you right here if you want to. I don’t accept invasions, missiles, or assassinations, only intel.”

He’s watched the pattern, recognised the trajectory, and decided that ambiguity serves Trump’s interests, not Colombia’s. By publicly daring Trump to act, he’s attempting to make the cost visible before the operation, not after.

Whether it works is unknowable. But it’s based on clear-eyed pattern recognition, not denial.

Also worth noting: Petro is Colombia’s first left-wing leader in modern history. Trump’s not randomly threatening countries. He’s systematically targeting left-wing governments whilst backing right-wing leaders like Argentina’s Javier Milei and pardoning ex-Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández of drug trafficking charges.

The pattern isn’t about drugs. It’s about political alignment. The drugs are just the permission structure—the linguistic wrapper that makes intervention sound like law enforcement instead of what politicians actually do when they’ve got something to sell: they sell it. Not just themselves—entire countries, their resources, their sovereignty. And the question nobody’s asking in public is: who’s buying?

What You Can Document vs What You Can’t Predict.

I can’t tell you which country Trump hits next Tuesday. His unpredictability is part of the control mechanism—if everyone’s guessing targets, nobody’s organising against the pattern itself.

But I can document what’s mathematically certain:

The rhetoric-to-action gap has closed. Trump threatened Maduro, then grabbed him. Threatened Petro. Colombia knows what that timeline looks like now.

Each escalation expands tomorrow’s possibilities. What seems unthinkable today becomes Tuesday’s policy discussion after one successful operation.

International law is now theatre. Multiple nations called Venezuela a violation of fundamental principles. Zero consequences followed. The rulebook’s still there—it’s just decorative now.

The pretext is fungible. Drugs, minerals, security, democracy, humanitarian concerns—pick any card. They all lead to the same door.

And here’s the bit that’s worth sitting with: roughly 80% of what’s happening is noise—statements, condemnations, diplomatic theatre. But about 20% of the actors and actions are driving all the meaningful outcomes. Trump’s threats, Petro’s challenge, the actual military operations. Everything else is just people being busy whilst the boundaries actually shift.

The UK Bit Everyone’s Ignoring.

British readers watching this and thinking “that’s America being America” are missing the structural lesson.

This is what happens when the gap between stated rules and actual consequences becomes a canyon. When international agreements become performance rather than binding. When “we don’t do that” stops being a line and becomes nostalgia.

The mechanics are identical whether you’re watching Trump threaten Colombia or watching UK institutions fail their own accountability standards. Different scale, same mathematics.

Rules only work when breaking them costs something. The moment enforcement becomes optional, you’re not operating under rules—you’re operating under suggestions that powerful people can ignore when convenient.

Sound familiar? Bristol City Council promising 1,000 new homes whilst selling 1,222 existing ones. Implementing schemes despite 54% resident opposition. Systematically violating FOI law. Same pattern—stated commitments becoming decorative whilst actual behaviour runs unopposed.

Rules without enforcement are just performance art with better stationery.

Petro’s Real Warning.

The most interesting bit in Petro’s response wasn’t the “come get me” line. It was this:

“If you bomb even one of these groups without sufficient intelligence, you will kill many children. If you bomb peasants, thousands will turn into guerrillas in the mountains. And if you detain the president, whom a good part of my people love and respect, you will unleash the popular jaguar.”

He’s not threatening military resistance Colombia couldn’t win. He’s warning about consequences Trump hasn’t modelled: What happens after your operation succeeds?

Because here’s the thing about Colombia: it faces a six-decade-long internal conflict between government forces, left-wing rebels, right-wing paramilitaries and criminal networks.

You remove Petro, then what? Who governs? What fills the vacuum?

The operation is the easy bit. It’s the autopsy that gets complicated.

This is where competence becomes visible. Great at conducting raids? Excellent. But governing the aftermath requires different skills entirely. Success in one domain doesn’t guarantee competence in the next. And when people get promoted beyond their actual capabilities—when the job requires judgment they demonstrably lack—that’s when the real disasters start.

Three Questions, Final Analysis.

Is it practical?

Yes. Venezuela proved capability. Colombia produces nearly 253,000 hectares of coca and borders Venezuela. The infrastructure exists.

Is it logical?

Only if you believe abducting heads of state produces stable outcomes. History suggests otherwise, but logic and policy divorced years ago.

What’s the likely outcome?

Short-term: Another “successful operation,” another captured leader.

Medium-term: Regional destabilisation, power vacuum, refugee crisis.

Long-term: Normalisation of military intervention as standard policy tool.

But here’s what’s certain: whatever happens with Colombia sets the baseline for what comes next. Every action that goes unchallenged becomes the new floor, not the ceiling.

The Documentary Record.

I’m not predicting Trump invades Colombia next Tuesday.

I’m documenting the scaffolding that makes “Trump invades Colombia next Tuesday” a sentence you can read without thinking I’ve lost the plot.

That’s the actual story.

Not where the pin lands on the map—but that we’re throwing pins at maps and calling it foreign policy.

Not which country gets threatened next—but how threatening sovereign nations became normal conversation.

Not predicting the future—but autopsying how this present became possible.

The Punchline.

Petro: “Come get me, coward.”

Trump: “Sounds good to me.”

Now we watch the gap between those two statements close.

Because that gap—between words and bombs, threats and action, rhetoric and consequences—that’s where the real story lives.

And it’s closing faster than international law can pretend to matter.

Welcome to 2026, where heads of state dare superpowers on social media and the superpowers say “cheers for the target confirmation.”

If you’re not documenting this in real-time, you’re already behind the pattern.

The Almighty Gob is an independent blogger and satirical commentator tracking institutional accountability and power mechanics. Subscribe for pattern recognition before the pattern recognises you.

Follow: thealmightygob.com | @thealmightygob

Sources.

Al Jazeera: “’He’ll be next’: Donald Trump threatens Colombian President Gustavo Petro” (11 December 2025)

CNN en Español: “El impacto político en Colombia de las amenazas de Trump” (5 January 2026)

Euronews: “Colombian president ready to ‘take up arms’ in face of Trump threats” (5 January 2026)

Axios: “War of words between Trump and Colombia’s Petro escalates” (5 January 2026)

Al Jazeera: “Trump threatens Colombia’s Petro, says Cuba looks ‘ready to fall’” (5 January 2026)

Yahoo News: “Colombia President Gustavo Petro Taunts Trump: ‘Come Get Me, I’m Waiting’” (5 January 2026)

Multiple sources documenting the escalating tensions and Trump’s systematic targeting of left-wing governments

References

Nabaz Tagavi: “A politician is just another form of prostitute — but in politics. They are political prostitutes. The difference is, they sell not only themselves, but also their country and everything else.” (The Shabak: A People Without Rights, 2003)

The Pareto Principle (Vilfredo Pareto): In many contexts, approximately 80% of effects come from 20% of causes.

Hanlon’s Razor: Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.

The Peter Principle (Laurence J. Peter): In a hierarchy, people tend to rise to their level of incompetence.