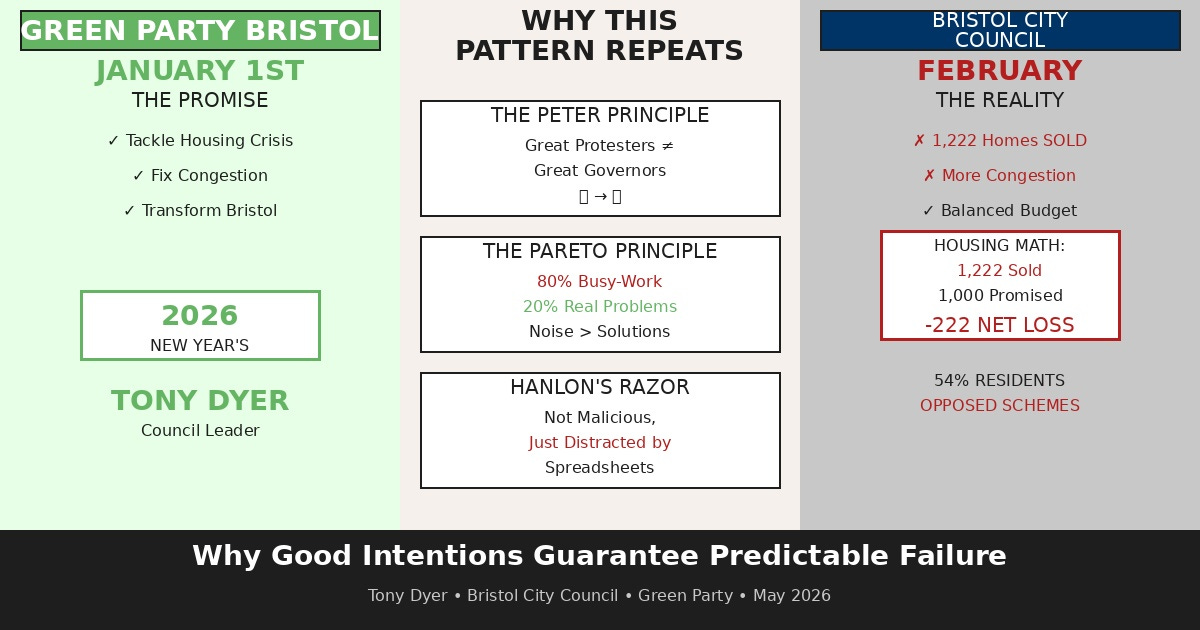

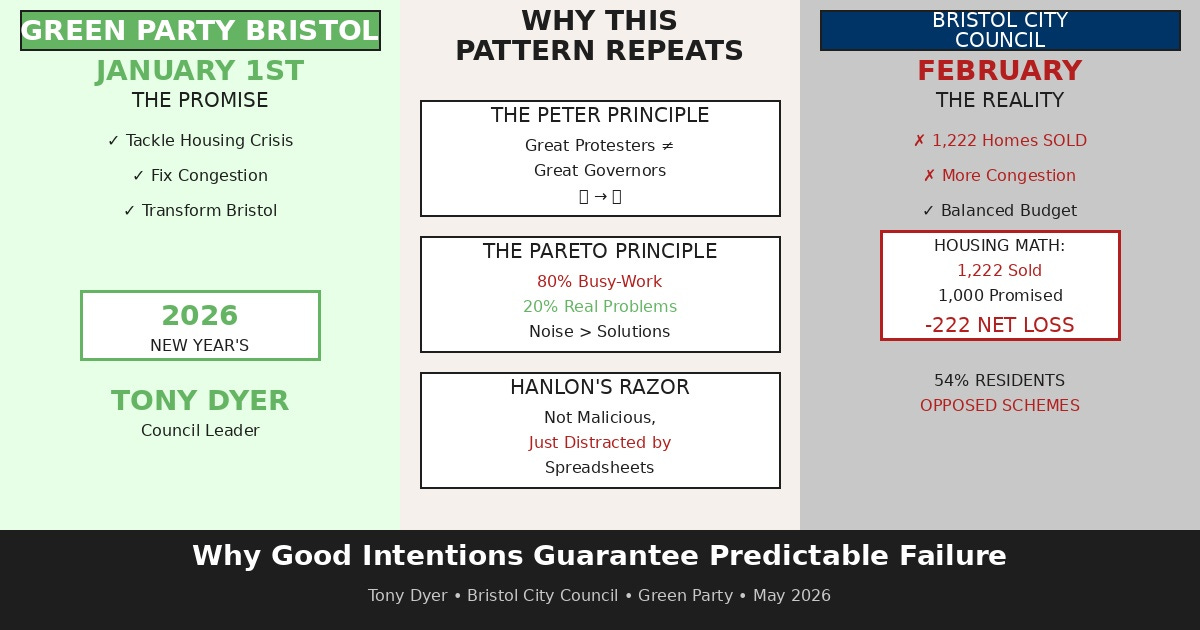

Dyer's New Year's Resolution: Tackle the Crises His Party Policies Created.

Why good intentions guarantee predictable failure.

You know that mate who starts every January promising to get fit, then spends February eating crisps on the sofa? Tony Dyer’s just given Bristol the political version.

The Green council leader’s revealed his “priorities” for 2026: tackling the housing crisis and congestion. Which would be encouraging if his administration wasn’t actively making both worse through policy choices that defy basic arithmetic.

Before we get into this, something you should know: I’m not a scholarly person. Left school at 15 with bugger all formal education. Everything I’ve learned, I’ve learned through living it from that point onwards. But somehow these quotes and principles just seem to land at exactly the right time when I’m writing—they capture everything I wanted to say but couldn’t quite articulate. Not because I’m superintelligent. Just that these things appear when needed, and suddenly the pattern I’ve been seeing makes perfect sense.

This is one of those times.

Three principles explain exactly why council leaders promise to solve crises while implementing policies that worsen them. The Peter Principle, the Pareto Principle, and Hanlon’s Razor aren’t abstract theory—they’re the operating system running Bristol City Council.

Let’s run this through the only questions that matter: Is it practical? Is it logical? What’s the likely outcome?

The Peter Principle: Great Protesters Don’t Always Make Great Governors

People rise to their level of incompetence. Success in one role doesn’t ensure competence in the next.

The Greens won seats by opposing things—developments, schemes, policies. Excellent at activism. Now they’re responsible for delivering things. Different skill set entirely. That’s the Peter Principle in action: great protesters don’t always make great governors, and the housing numbers prove it.

Dyer’s excited about “regeneration projects delivering many new homes.” Translation: private developers building market-rate housing on public land. Bristol already tried this. It doesn’t work.

The actual data: selling 1,222 council homes they already own while promising to build 1,000 new affordable homes annually. Basic subtraction shows they’re going backwards. Net reduction in social housing stock while declaring a housing emergency.

Temple Quarter and Western Harbour—Dyer’s flagship “regeneration” schemes—follow the standard formula: sell public assets to enable private profit, deliver statutory minimum affordable percentage, call it solving the crisis.

The Regulator of Social Housing flagged council homes in “shocking condition” shortly after the Greens took control. Their solution? Stop building new council housing to fix existing stock. Sounds reasonable until you remember they’re simultaneously selling 1,222 homes. That’s managed decline with better PR.

Practical? No. You can’t solve an affordable housing shortage by reducing affordable housing stock.

Logical? Only if you believe market mechanisms solve market failures.

Likely outcome? More displacement, continued crisis, developer profits, political theatre of “taking action.”

The Pareto Principle: Noise Masquerading as Productivity

80% of your results come from 20% of your actions. Most of what you do is just noise masquerading as productivity.

Bristol’s transport problems come from a few critical issues: unreliable buses, decayed infrastructure, population growth outpacing capacity. That’s the vital 20% needing attention.

What’s the council doing instead? Traffic calming measures that obstruct emergency services. Low Traffic Neighbourhoods creating traffic displacement. Transport schemes rolled out despite 54% resident opposition. All the 80% busy-work that looks like action while avoiding actual problems. That’s the Pareto Principle in action.

“Nobody’s happy with Bristol’s transport system,” Dyer admits. Refreshing honesty. Less refreshing: his administration implemented the schemes making people unhappy.

Now Dyer promises to “rebalance transport systems to improve public transport quality.” Which sounds great until you remember transport rebalancing IS what they’ve been doing. That’s the policy creating the congestion he’s now promising to fix.

The roadworks excuse is fascinating: “It’s annoying when you have roadworks, but those roadworks are necessary.” Translation: we ignored the vital 20% (preventative maintenance) while focusing on the 80% noise (ideological transport schemes). Now emergency intervention is inevitable.

Practical? Creating congestion through ideological schemes then promising to fix it isn’t problem-solving.

Logical? Only if focusing on the wrong 20% delivers results.

Likely outcome? More schemes majority oppose, continued congestion, blame deflection to infrastructure work.

Hanlon’s Razor: Never Attribute to Malice What Can Be Explained by Distraction.

People aren’t out to harm you; they’re just distracted.

The Greens aren’t deliberately making Bristol worse—they’re distracted by spreadsheet balancing while housing deteriorates, transport fails, and services degrade. Good intentions, wrong priorities. Focused on process (balanced budget) rather than outcomes (housed residents, functioning transport, thriving culture). That’s Hanlon’s Razor: not malice, just distraction.

Dyer’s “proudest achievement” is setting a balanced budget. Not improving lives. Not solving crises. Not delivering services. A balanced spreadsheet. That’s the tell. When process becomes achievement, outcomes become negotiable.

How’d they balance it? Cultural Investment Programme cuts (Aardman, Watershed, Bristol Beacon, Old Vic, Arnolfini opposing). Bristol Impact Fund reductions. Selling council housing.

“Our financial situation is better than it was last year,” Dyer boasts. Because they cut things. That’s not improvement—that’s sacrificing function for spreadsheet aesthetics.

The Parent Carer Forum scandal captures this perfectly. Three years ago they tried cutting funding and got caught spying on parents of disabled children’s social media. Monitoring thoughts. Spinoza called it centuries ago: “The most tyrannical of governments are those which make crimes of opinions, for everyone has an inalienable right to his thoughts.”

Now the relationship’s “much better, more collaborative.” The bar for improvement is literally “not spying on parents.” That’s the benchmark. Not malicious—just distracted from what actually matters.

The Improvement Claims Without Metrics.

Notice the language: “Services have started to show signs of improvement.” “We’re turning around areas that weren’t performing well.”

All perpetual journey language. No destination. No hard numbers. Just directional claims that can’t be falsified.

Watchdogs “recently found they have been improving”—from what baseline? What constitutes improvement? The Bristol Live article doesn’t say.

Children’s services, adult social care, temporary accommodation, planning, housing stock—all claimed as “significant improvements.” Zero metrics. Just trust the process.

What This Actually Is.

A Bristol Live puff piece four months before May elections. No challenging questions about contradictions. No follow-up on vague claims. No hard metrics. Dyer’s narrative presented uncritically.

Here’s the thing about timing: whether Dyer’s deliberately calculated this or stumbled into it, the effect’s the same. You don’t drop political messaging on election day and hope it sticks. Seeds get planted months in advance. By May, when voters see his name on the ballot, they’ll have this comfortable feeling—”Oh yeah, he’s the one tackling housing and congestion.” The association’s already made. The promise feels familiar, even though nothing’s been delivered.

Could be strategic planning from party apparatus. Could be Bristol Live independently positioning themselves as Green-friendly. Could be Dyer accidentally landing on effective timing. Doesn’t matter. The machinery works regardless of who’s driving.

Free campaign material dressed as journalism. The resolution genre: declared publicly with serious intent, sounds virtuous, requires no immediate action, creates no binding accountability, allows claiming credit for announcement itself.

January 1st matters because that’s when people are most receptive to aspirational messaging and least likely to scrutinise track records.

The Pattern You’re Meant to Miss.

Peter Principle + Pareto Principle + Hanlon’s Razor = This Exact Dysfunction

Activists promoted beyond competence (Peter) focusing on ideological busy-work instead of vital problems (Pareto) while genuinely believing spreadsheet balance equals success (Hanlon). Not conspiracy—predictable institutional failure.

Here’s what’s actually happening: identifying real problems while implementing policies that worsen them, then expressing concern about the problems.

Selling council homes = tackles housing crisis Implementing unpopular transport schemes = fixes congestion

Cutting services = improves financial situation Not spying on parents = relationship improvement

Three questions test:

Practical? Market mechanisms solving affordable housing = No. Ideological schemes fixing congestion = No.

Logical? Creating problems then promising to solve them = No.

Likely outcome? Continued crises with different rhetoric.

And like most New Year’s resolutions, the gap between aspiration and implementation is where the whole thing falls apart. But at least Dyer’s being honest about one thing: he’s very boring, and his number one priority is setting another balanced budget.

Which tells you everything about his actual values: bureaucratic process over human outcomes. Spreadsheet aesthetics over lived reality. The announcement over the achievement.

Bristol deserves better than political resolutions that dissolve by February. But you don’t get what you deserve—you get what you tolerate.

Sources:

Bristol Live (2026). “Tackling Bristol’s housing crisis and congestion among council leader’s hopes for 2026.” Bristol Live, 1 January.

Regulator of Social Housing (2024). Report on Bristol City Council housing stock conditions.

Bristol City Council (2024). Housing Stock Disposal Programme documentation.

Bristol City Council (2024). Budget Balance Report, February.

Parent Carer Forum Bristol (2021-2024). Documentation of funding controversy and relationship rebuild.

Peter, L.J. & Hull, R. (1969). The Peter Principle: Why Things Always Go Wrong. William Morrow and Company.

Pareto, V. (1896). Cours d’économie politique. University of Lausanne.

Hanlon, R. (1980). “Hanlon’s Razor.” Cited in Murphy’s Law Book Two (1980).

Spinoza, B. (1670). Tractatus Theologico-Politicus.