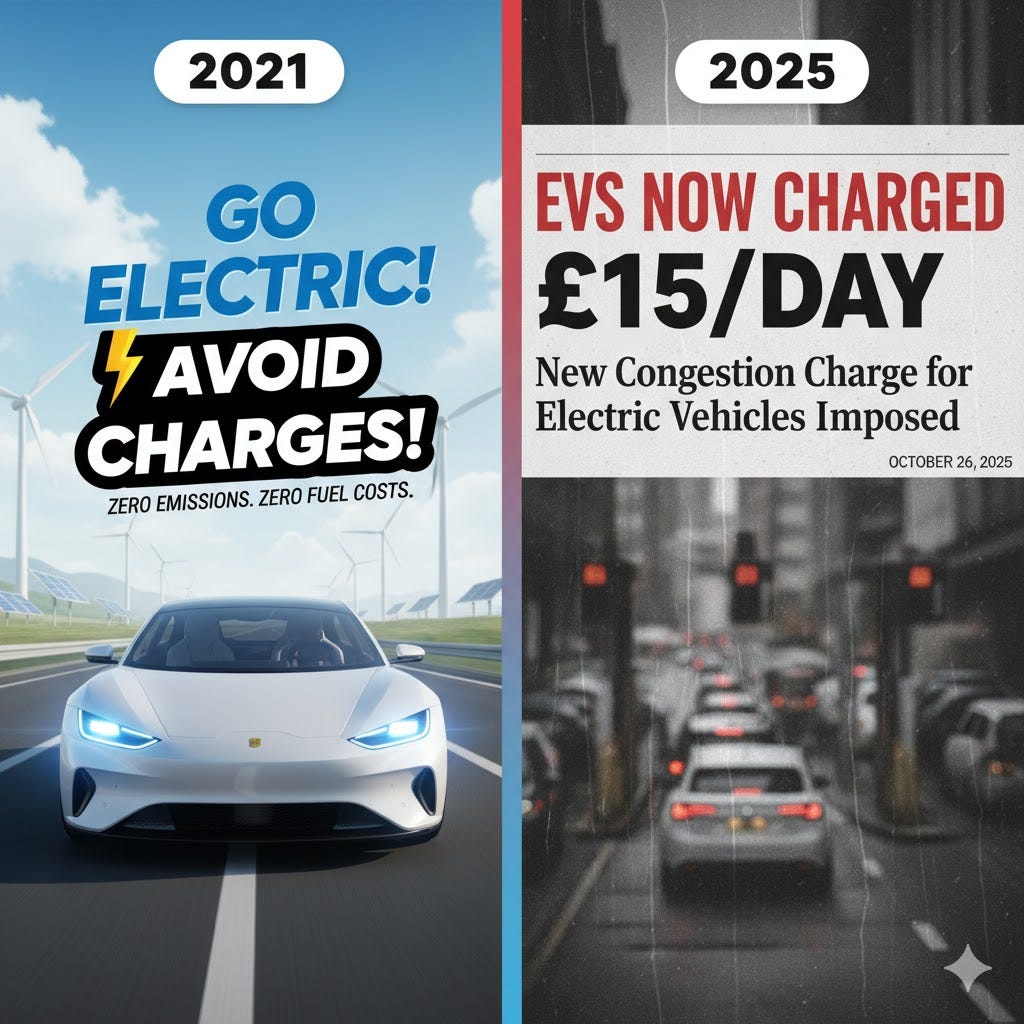

The Electric Vehicle Scam: How British Cities Championed EVs Then Penalised the Drivers Who Believed Them.

London's £15-a-Day Christmas "Present" Reveals the Real Game.

Bottom Line Up Front: British cities spent years championing electric vehicles as the solution to pollution, offering exemptions and incentives to drive adoption. Now that drivers have made the switch in good faith, those same authorities are systematically removing every benefit and introducing new charges. London will hit EV drivers with £15 daily congestion charges from Christmas Day 2025, Bristol is hiking Clean Air Zone fees by up to 55%, and the UK government is planning a 3p-per-mile tax on EVs by 2028. This isn’t policy evolution—it’s a bait-and-switch scam that proves these schemes were never about the environment. They were always about revenue.

The Bait: “Go Electric, Save the Planet!”

Remember when going electric made you a hero? When cities painted you as part of the solution, not the problem? When local authorities championed electric vehicles as the answer to urban pollution and climate change?

That wasn’t very long ago. In fact, it was the entire justification for Clean Air Zones, Ultra Low Emission Zones, and congestion charges across British cities. The narrative was simple: switch to electric, and you’ll be rewarded with exemptions, reduced charges, and the moral satisfaction of saving the planet.

Bristol City Council brought in its Class D Clean Air Zone in November 2022, charging older diesel and petrol vehicles £9 daily to enter the city centre. Electric vehicles? Completely exempt. The same story played out in London, where Sadiq Khan introduced the Cleaner Vehicle Discount in 2021, allowing EV drivers to pay just £10 annually instead of the standard £15 daily congestion charge.

The message was clear: buy electric, and we’ll make it worth your while.

Birmingham’s Clean Air Zone exempted EVs entirely. Bath’s Class C zone did the same. Cities across England created a two-tier system where electric vehicles received preferential treatment, explicitly designed to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels.

And it worked. Drivers believed them. Between 2019 and 2024, the number of vehicles registered for London’s Cleaner Vehicle Discount alone jumped from 20,000 to over 112,000. People made financial decisions—often significant ones—based on the incentives their local authorities promised.

They switched. They invested. They believed the deal would last.

The Switch: “Actually, You’re the Problem Now.”

Here’s where it gets interesting. Now that drivers have actually made the switch, local authorities have suddenly discovered that electric vehicles are somehow also a problem.

London: The £15-a-Day Christmas “Gift”

On Christmas Day 2025, Transport for London will end the Cleaner Vehicle Discount entirely. Those 112,000 EV drivers who were paying £10 annually? They’ll now pay the full £15 daily congestion charge—the same rate as every petrol and diesel vehicle they were told to replace.

For someone commuting into central London five days a week, that’s £3,900 per year. Plus the £195 annual road tax that EVs started paying in April 2025. Plus the proposed 3p-per-mile tax expected from 2028, which would add another £250-£360 annually for average drivers.

Transport for London’s justification? They claim it’s necessary to “maintain the effectiveness of the Congestion Charge” and “manage traffic congestion.” Which is a fascinating admission when you think about it: if electric vehicles contribute to congestion, they always did. The pollution was never the actual problem they were trying to solve.

Sadiq Khan himself introduced the EV exemption specifically to encourage the switch to electric. Now his own transport authority claims that exemption is undermining the scheme’s effectiveness. The only thing that’s changed is the number of drivers who believed him.

As AA president Edmund King told the BBC, this is “a backward step which sadly will backfire on air quality in London” because “many drivers are not quite ready to make the switch to electric vehicles, so incentives are still needed.”

Translation: removing incentives the moment people respond to them guarantees nobody will trust future incentives. Why would they?

Bristol: The Green Dream Meets Reality.

Bristol’s story is even more instructive because the city is run by the Green Party—the people who are supposed to really believe in this stuff.

The city’s Clean Air Zone brought in £31.2 million in its first year while claiming pollution reductions. Electric vehicles remained exempt, positioned as the virtuous alternative to polluting diesels.

Fast forward to November 2025, and Bristol City Council is considering raising the daily charge from £9 to as much as £14—a 55% increase. Their justification? “Rising inflation, shifts in travel behaviours, and smaller reductions in NO2 in 2024 than in 2023 suggest the current charges may no longer act as a strong deterrent.”

Read that again. The charges are working too well. People have actually changed their behaviour, which means fewer people are paying the charge, which means less revenue, which means the charges need to increase to “maintain effectiveness.”

And here’s the kicker: Bristol is facing a £52 million funding gap, and council officers are seeking government permission to raise Clean Air Zone fees specifically to help plug that hole. The council openly admits that while raising charges would bring in an extra £200,000 annually in 2026/27 and 2027/28, they expect that income to drop off again as more vehicles become compliant—resulting in a net gain of zero pounds.

So they’ll raise charges on drivers they encouraged to switch, knowing it won’t actually solve their budget crisis, because the whole point was never pollution reduction. It was revenue generation that happened to come with a convenient environmental narrative.

The National Pattern: It’s Not a Bug, It’s the Business Model.

This isn’t isolated incompetence. It’s a coordinated pattern playing out across multiple cities:

Birmingham runs a Class D Clean Air Zone charging non-compliant vehicles £8 daily, with EVs exempt. But watch this space.

Bath operates a Class C zone that doesn’t charge private cars—yet. The infrastructure is there. The precedent is set. The playbook is written.

Bradford, Portsmouth, Sheffield, and Tyneside all have Clean Air Zones with similar exemptions for electric vehicles. Every single one represents future revenue potential the moment those exemptions become “unsustainable” or “less effective.”

The pattern is identical everywhere:

Identify pollution as a crisis requiring immediate action

Introduce charging zones that exempt electric vehicles

Encourage drivers to switch to electric to avoid charges

Wait for enough drivers to actually switch

Remove exemptions because “electric vehicles contribute to congestion too”

Introduce additional charges because “we need to maintain revenue streams”

The Real Tell: Follow the Money.

If these schemes were genuinely about pollution and public health, the cities implementing them would be celebrating victory as compliance rates increase. They’d be declaring mission accomplished as electric vehicle adoption accelerates.

Instead, they’re panicking about revenue shortfalls.

London’s congestion charge has generated £2.6 billion since 2003, with about £1.2 billion invested in public transport improvements. That’s a substantial revenue stream to protect. As 20% of vehicles entering the zone are now electric, that’s 20% of potential daily charges not being collected.

Bristol explicitly admits the financial motive. When explaining potential fee increases, council documents state the charges “may no longer act as a strong deterrent” because compliance is increasing. They’re literally saying the policy is working too well from an environmental perspective, so it needs to be adjusted from a financial perspective.

At the national level, the Treasury’s concerns are even more transparent. Fuel duty currently generates £25 billion annually—money that disappears as drivers switch to electric. With 1.3 million EVs already on UK roads and projections of six million by 2028, the Treasury faces a potential £7-30 billion shortfall by 2030 without intervention.

Hence the proposed 3p-per-mile road pricing for EVs expected to be announced in the November 2025 Budget, with implementation from 2028. This would see EV drivers estimate their annual mileage upfront and pay accordingly, potentially raising £1.8 billion annually by 2031.

The environmental benefits of electric vehicles haven’t changed. What’s changed is that people actually responded to the incentives, and now the revenue models don’t work anymore.

The Cynicism Test: What If They’d Been Honest?

Imagine if, back in 2021 when London introduced its EV exemption, Sadiq Khan had said this instead:

“We’re offering electric vehicles a temporary exemption from the congestion charge to help accelerate adoption. This exemption will last approximately four years, until December 2025, at which point all vehicles will pay the standard rate. We’re being transparent about this timeline so drivers can make informed decisions about whether switching to electric makes financial sense for them.”

Or if Bristol City Council had announced their Clean Air Zone like this:

“We’re introducing charges for older diesel and petrol vehicles. Electric vehicles will initially be exempt to encourage adoption, but we reserve the right to charge them in future and may increase fees when our budget requires it, regardless of pollution levels.”

The honesty would have been refreshing. It also would have resulted in far fewer people making the switch, because the value proposition would have been transparently terrible.

So they weren’t honest. They created the impression of lasting benefits. They allowed drivers to believe that going electric was a long-term solution, not a four-year promotional offer.

The Industry Response: Mixed Messages and Mission Failure.

Even the automotive industry—which supposedly benefits from EV sales—is warning this approach is catastrophic.

The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders called the proposed pay-per-mile tax an “entirely wrong measure”, stating that “introducing such a complex, costly regime that targets the very vehicles manufacturers are challenged to sell would be a strategic mistake—deterring consumers and further undermining industry’s ability to meet ZEV mandate targets.”

AA president Edmund King warned the government needs to “tread carefully unless their actions slow down the transition to EVs,” calling it a potential “poll tax on wheels.”

Ginny Buckley, founder of Electrifying.com, said: “You can’t drive the EV transition with one foot on the accelerator and the other on the brake. Public charging is already more expensive per mile than petrol for some users.”

Oliver Lord, UK Head of Clean Cities, told Cities Today: “It’s puzzling this incentive is being taken from small businesses who rely on polluting diesel vans and need the most help to go electric. Now is not the right time for the Mayor to axe this vital support.”

Even the people whose business models depend on EV adoption are saying the government’s approach is self-defeating. That should tell you everything.

The Bristol Green Party: When True Believers Become Pragmatists.

Bristol deserves special attention because it’s run by the Green Party—people who theoretically should be prioritizing environmental outcomes over revenue generation.

And yet here they are, proposing to increase Clean Air Zone charges while facing a massive budget deficit, using language about “deterrence” and “compliance” that sounds identical to every other local authority concerned primarily with money.

This is what happens when theoretical principles meet fiscal reality. When opposition rhetoric meets governing responsibility. When the people who criticised others for not caring enough about the environment discover that environmental policies cost money and generate revenue conflicts.

The Bristol Greens spent years positioning themselves as the alternative to business-as-usual politics. They campaigned on holding others accountable for environmental commitments. They built their brand on being the party that would actually follow through on climate action without compromise.

Now they’re governing, and suddenly they sound exactly like every other council desperately trying to plug budget holes. The pollution reductions are slowing down? Raise charges. The revenue isn’t meeting projections? Adjust the fees. The budget gap is growing? Well, we’ve got this Clean Air Zone generating £31 million annually—let’s optimise that revenue stream.

The transformation is instructive: when Greens govern, they govern like everyone else. Because when you’re responsible for bin collections, social care, road maintenance, and keeping the lights on, environmental ideals compete with dozens of other urgent priorities. And revenue always wins.

Which raises the obvious question: if the Green Party can’t maintain environmental priorities when they’re actually in power, why should anyone believe any party’s environmental commitments?

The Trust Equation: Why This Matters Beyond EVs.

This isn’t just about electric vehicles. It’s about institutional credibility and whether citizens can trust government commitments when making major financial decisions.

Electric vehicles are expensive. A new EV typically costs £30,000-£60,000. People who switched based on promised exemptions and incentives made substantial financial commitments in good faith. They believed local authorities when they said “this is the future, and we’ll support you for making this choice.”

Now those people are discovering the support was temporary, the exemptions were conditional, and the real purpose was always revenue optimisation, not environmental improvement.

What happens next time government wants to encourage behaviour change? Why would anyone believe new incentives will last? Why would businesses invest in infrastructure based on government promises? Why would individuals make expensive decisions based on policy commitments?

Trust, once broken, is extraordinarily difficult to rebuild. And British institutions are systematically breaking trust with people who believed them and acted accordingly.

The pay-per-mile tax is particularly instructive here. Reports indicate EV drivers would be asked to estimate their annual mileage and pay upfront, with adjustments if they drive more or less. This is the government literally asking people to self-report their behaviour in a system explicitly designed to extract more money from them.

Who, exactly, is going to voluntarily over-estimate? Who’s going to accurately report when under-reporting saves hundreds of pounds? The system assumes a level of civic cooperation that the government itself has just destroyed by pulling the rug out from under early EV adopters.

The Real Climate Implications: Self-Sabotage at Scale.

Here’s the darkly hilarious part: this approach actively undermines the environmental goals it supposedly serves.

The UK government has legally binding commitments to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. The ban on new petrol and diesel car sales by 2035 is explicitly tied to that target. The theory is that if you stop selling fossil fuel vehicles by 2035, and cars typically stay on the road for 15 years, the UK car fleet will be largely electric by 2050.

But that only works if people actually buy electric vehicles. And people won’t buy electric vehicles if they believe the government will immediately remove every benefit and add new charges the moment adoption reaches critical mass.

The ZEV (Zero Emission Vehicle) mandate requires 22% of sales to be electric in 2025, rising to 80% by 2030. Car manufacturers face fines if they miss those targets. But as Autocar points out, introducing a pay-per-mile tax in 2028—right when manufacturers need to hit 52% market share—will “hit consumer confidence, causing future crashes.”

So the government is legally bound to reach net-zero, has mandated EV adoption to achieve it, but is actively implementing policies that discourage EV adoption. It’s self-sabotage at a scale that would be impressive if it weren’t so consequential.

And the biggest loser, as Autocar correctly identifies, won’t be car manufacturers or EV drivers—it’ll be the government itself when it faces legal action for failing to meet its own legally binding climate commitments because its revenue priorities undermined its environmental policies.

The European Context: Are Other Countries This Cynical?

The UK isn’t alone in facing the revenue challenge created by EV adoption, but it’s notable how other European countries are handling it.

Norway, which has the highest EV adoption rate in Europe, has maintained relatively stable incentives while gradually introducing modest charges. The approach has been transparently staged, with long advance notice of changes.

The Netherlands has been explicit about the temporary nature of some incentives from the start, allowing drivers to make informed decisions.

Germany has focused on infrastructure investment alongside purchase incentives, creating value that persists even as direct subsidies phase out.

The UK’s approach—promising exemptions, encouraging adoption, then systematically removing benefits while adding new charges—is distinctly more cynical. It’s not that other countries aren’t also concerned about revenue. It’s that they’ve generally been more honest about the trade-offs and timelines involved.

When Peter Barden’s analysis notes that “there are currently no plans to make the change to charge fully electric vehicles to use zones in the like of Bristol, Birmingham and Oxford, but with councils looking for ways to boost incomes – it’s a case of ‘watch this space,’” he’s describing a system where exemptions are temporary marketing tools, not genuine policy commitments.

What Should Have Happened: The Honest Approach.

There was a better way to do this. It required honesty, long-term thinking, and accepting short-term revenue losses for long-term environmental gains. Which is probably why it didn’t happen.

Here’s what an honest approach would have looked like:

1. Be explicit about timelines: When introducing EV exemptions, state clearly how long they’ll last. “This exemption will remain in place until 2030” gives people information to make informed decisions.

2. Structure incentives that add value, not just remove costs: Instead of temporary exemptions, invest in charging infrastructure, dedicated lanes, priority parking—benefits that persist and make EV ownership genuinely better.

3. Accept revenue transition costs: Yes, fuel duty will decline. Yes, congestion charge revenue will change. Plan for this in advance rather than panicking when people respond to your incentives.

4. Implement broad-based road pricing fairly: If you need road pricing, apply it to all vehicles from the start, with lower rates for cleaner vehicles, so nobody feels like they’ve been scammed after making expensive commitments.

5. Maintain some EV advantages: Even if you need to charge EVs, charge them less than fossil fuel vehicles if pollution is genuinely part of your concern.

None of this happened because it would have required long-term thinking and short-term revenue sacrifice. Much easier to get people to switch with false promises and then change the rules once they’re committed.

The Bottom Line: It Was Always About the Money.

Every electric vehicle on the road represents lost fuel duty, lost congestion charge revenue, lost parking revenue. That was always true. It was true when cities introduced exemptions. It was true when local authorities encouraged people to switch. It was true when the government set EV adoption targets.

What’s changed isn’t the environmental calculus or the fiscal reality. What’s changed is that people actually believed them and responded accordingly, and now the revenue implications are real rather than theoretical.

The environmental benefits of EVs haven’t diminished. They still produce zero tailpipe emissions. They’re still better for air quality in urban areas. They’re still essential for meeting climate targets.

But they never pay fuel duty. They never generate the constant, predictable revenue stream that petrol and diesel vehicles produce. And when you get right down to it, that’s what actually mattered.

London’s congestion charge was introduced in 2003 explicitly to reduce traffic and improve air quality, with revenue as a secondary benefit. Twenty-two years later, with 20% of vehicles in the zone now electric, the city is ending EV exemptions precisely because those vehicles reduce revenue while still contributing to “congestion.”

Which proves congestion was never the real target. If it were, you’d celebrate fewer vehicles, regardless of propulsion type. If air quality were the real target, you’d celebrate zero-emission vehicles. If environmental improvement were the real target, you’d be declaring victory.

Instead, you’re scrambling to restore revenue streams by charging the very vehicles you encouraged people to buy. Because the revenue was always the point. The environmental messaging was marketing. The exemptions were promotional offers. And now the promotion is over.

What This Means for Bristol: Your Green-Led Council’s True Priorities.

Bristol residents deserve to understand exactly what’s happening in their own city. Your Green-led council is considering raising Clean Air Zone charges by up to 55%—from £9 to potentially £14 daily—explicitly because compliance is increasing and pollution is reducing.

Let that sink in. The scheme is working environmentally, so they’re increasing charges financially.

And they’re doing this while facing a £52 million budget deficit, openly admitting that raising CAZ charges will bring in extra money short-term but result in zero net gain long-term as more vehicles become compliant.

This is your Green Party council. The party that’s supposed to be different. The party that’s supposed to prioritise environmental outcomes over revenue generation. The party that spent years criticizing others for not taking climate action seriously enough.

And when they’re in power, they sound exactly like every other cash-strapped local authority desperately trying to balance books by squeezing revenue from whatever sources are available—including the people who switched to cleaner vehicles specifically because the council encouraged them to.

If the Greens can’t maintain environmental priorities when governing, who can? If the party whose entire brand is built on environmental commitment will compromise those commitments for budget management, why should anyone believe any party’s environmental promises?

Bristol’s story is the perfect microcosm of the broader pattern: encourage behaviour change, benefit from the environmental improvements, then charge people for having changed their behaviour because you need the revenue. Dress it up in language about “deterrence” and “compliance” and “effectiveness,” but it all means the same thing: we need the money, and you’re going to pay it.

Conclusion: The Lesson Nobody Wanted You to Learn.

The electric vehicle scam isn’t complicated. Cities and national government encouraged people to switch to EVs with promises of exemptions and incentives. People believed them and made expensive commitments accordingly. Now those exemptions are being systematically removed and new charges added, because the real goal was always revenue, not environment.

Three clear lessons emerge:

1. Environmental policy is cover for revenue policy. When government says “go green and we’ll reward you,” what they mean is “go green until enough of you do it that we need to monetise you too.”

2. Incentives are temporary marketing, not policy commitments. Any benefit offered to encourage behaviour change will be removed the moment that behaviour change is successful enough to impact revenue.

3. Trust, once destroyed, doesn’t rebuild. The next time government wants to encourage expensive behaviour change with promises of lasting benefits, people will remember London’s Christmas Day 2025 betrayal and Bristol’s 55% fee hike when pollution was actually decreasing.

From January 2, 2026, London EV drivers will pay £15 daily—or £18 after that date based on announced increases. Bristol drivers might pay £14 daily just to enter their own city centre. And by 2028, all UK EV drivers will likely pay an additional 3p per mile on top of £195 annual road tax.

The 112,000 drivers who believed Khan when he said switching to electric would be rewarded? They just learned that “reward” meant “temporary promotional offer, terms subject to change without notice, all benefits may be withdrawn when convenient.”

This wasn’t incompetence. It wasn’t policy evolution. It wasn’t unforeseen circumstances. It was exactly what anyone paying attention should have expected: institutions prioritizing revenue over every other consideration, using environmental language to disguise financial motives, and betraying people who believed them the moment it became fiscally convenient.

The only surprising thing is that anyone is surprised.

Welcome to British governance in 2025, where the only thing greener than the environmental commitments is the revenue stream they were always designed to protect.

If you found this article valuable and want to support independent political analysis that holds power to account, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Every subscription helps fund the research and writing that mainstream media won’t touch. Your support matters.

Really good points. I'm wondering if you could edit this to make it a lot shorter, or provide a shorter version to share?